Missouri in the News: The Birth of the State of Missouri from the Pages of the National Intelligencer

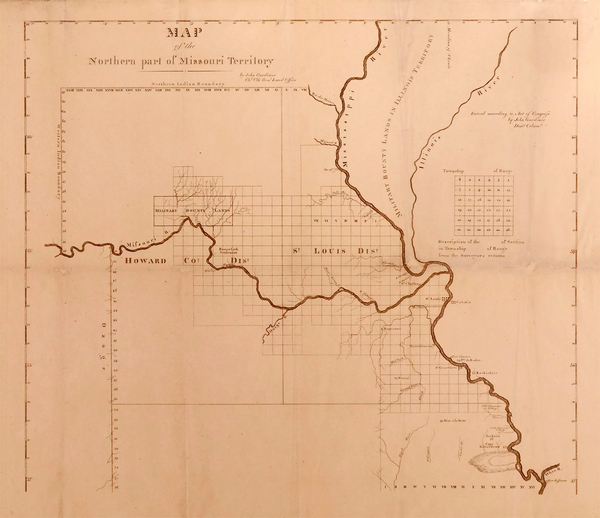

While many congressional arguments centered on the imbalance of power between free and slave states, some congressmen highlighted their moral opposition to Missouri’s admission as a slave state. An example can be seen in this excerpt of a speech by Congressman John W. Taylor of New York. He believed that Congress had “a moral and constitutional right” to prevent the spread of slavery to Missouri, which many feared could lead to slavery’s continual spread through the United States’ western territories. Congressman Taylor’s speech featured here ominously predicted that should slavery be allowed in Missouri, Congress’ inaction would torment future generations of Americans.

It is essential to note that during the Civil War, the Mercantile Library was the site on which the Emancipation Proclamation was ratified; thus resolving a forty year delay in freeing Missouri to grow without slavery.

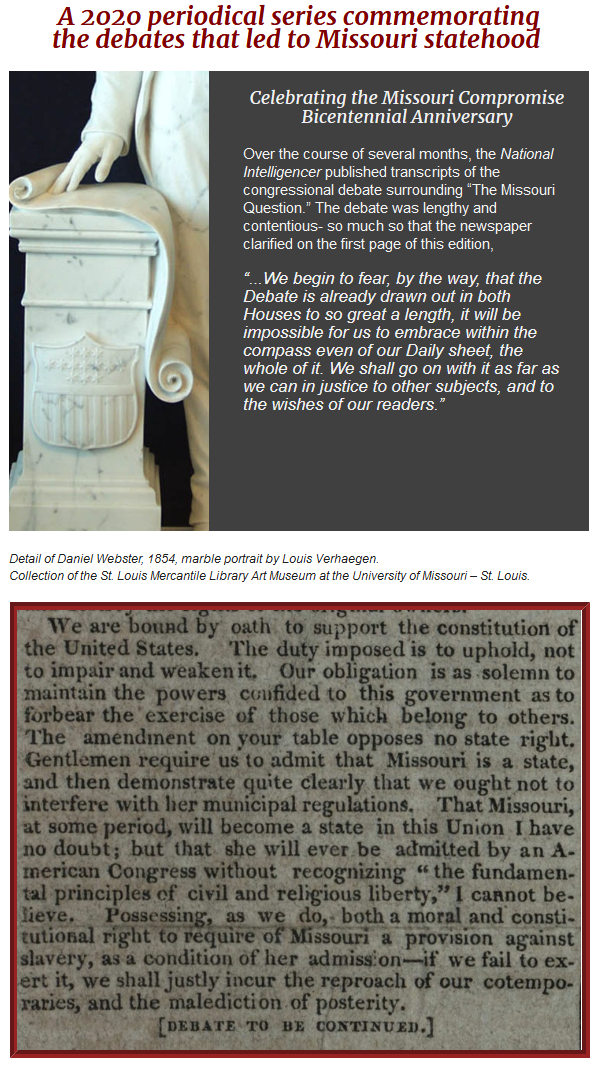

Map of the Northern Missouri Territory in 1817 (St. Louis Mercantile Library Collection)

The Missouri Question was one of the dominant political issues of the 1819-1820 Congressional Session. The preservation of the balance of power between free and slave states led to the creation of the Missouri Compromise of 1820 under the leadership of Speaker of the House Henry Clay of Kentucky. Clay's compromise allowed for the admission of Missouri and Maine and set a boundary on the expansion of slavery in the territories of the United States.

After the compromise went into effect, the territories of Maine and Missouri each had admission bills that had to be approved by the United States Congress before they could finally be admitted as states. When Missouri's admission bill came up for consideration, a clause involving the exclusion of free African-Americans caused the bill to be stopped in Congress. Clay crafted another compromise by effectively preventing this exclusionary clause from being applied against United States Citizens. After this bill was passed and signed into law by President James Monroe, Missouri would be officially admitted to the Union on August 10, 1821.

We will update this page regularly with new issues of The National Intelligencer during the bicentennial.

Follow the debate in the issues of The National Intelligencer:

The First Missouri Compromise Bill:

January 27, 1820

January 29, 1820

February 1, 1820

February 3, 1820

February 9, 1820

February 10, 1820

February 12, 1820

February 15, 1820

February 17, 1820

February 19, 1820

February 22, 1820

February 26, 1820

February 29, 1820

March 2, 1820

March 9, 1820

March 11, 1820

March 25, 1820

April 29, 1820

May 02, 1820

May 04, 1820

May 06, 1820

May 11, 1820

May 23, 1820

May 27, 1820

May 30, 1820

June 01, 1820

June 03, 1820

June 20, 1820

June 22, 1820

June 24, 1820

June 27, 1820

June 29, 1820

July 01, 1820

July 11, 1820

If you want to read ahead and view the entire digitized collection of The National Intelligencer, go here.