The Crockett Almanackswere first published for the year 1835 and included astronomical calculations “for all States in the Union” in addition to short essays on various wild animals inhabiting the West, biographical essays about Crockett and other stories. As shown in the section on almanac history, many almanacs were localized, providing astronomical and weather information for a limited geographical area. The inclusion in the Crockett Almanacks of information for the entire country is often cited as evidence of the widespread audience for which these books were intended. The entire series of Crockett Almanacs, which ran through 1856, was published with a wide variety of place-names on the cover, including Boston, Albany, Buffalo, New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Richmond, Louisville, Nashville and New Orleans. This broad geographical range of cities indicates the extent to which the Almanacks were distributed east of the Mississippi River. By the end of the Almanack series in the 1850s, the astrological calculations included Canada - a further indication of the high aims of the printers for distribution of this book. |

|

The 1830 editions, published with a Nashville imprint, are characterized by a folksy, if occasionally slightly off-color, humor interspersed with factual, informative material. Typical stories in the 1830s include “Davy Crockett’s Early Days, Severe Courtship and Marriage” (1835) that relates tales of Crockett’s youth and early courtships in an entertaining but fairly straightforward manner. Crockett’s first love was particularly memorable: “For though I have heard people talk about hard loving, yet I reckon no poor devil in this world was cursed with such hard love as mine has always been, when it came on me. I soon found myself head over heels in love with this girl; and I thought that if all the hills about there were pure chink, and all belonged to me, I would give them if I could just talk to her as I wanted to; but I was afraid to begin, for when I would think of saying anything to her, my heart would begin to flutter like a duck in a puddle; and if I tried to outdo it and speak, it would get right smack up in my throat, and choke me like a cold potato.” When Crockett does manage to convey his ardent feelings to the young girl, she confesses she is engaged to another, which sent our hero into a sickness, “it was the worst kind of sickness, - a sickness of the heart and all the tender parts, produced by a disappointed love.” The 1837 edition includes the tales of “Perilous Adventure with a Black Bear” and “Fatal Bear Fight on the Banks of the Arkansaw (sic).” The factual information also continued, as in the astrological charts and the essay “Method of Catching Wild Horses on the Prairies of Texas.”

|

|

|

|

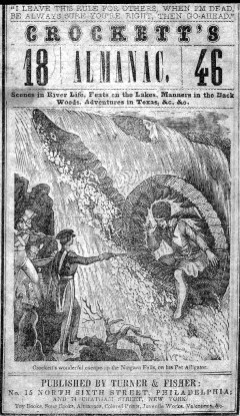

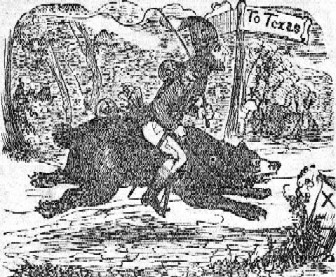

In the 1840s the printing was taken over by Turner & Fisher, and although this may be the most widely circulated edition, a significant change in tone occurs in the entertaining reading. The humor becomes more aggressive, with more overtly racial references and frequent use of scatological humor. Crockett himself is portrayed as the buffoonish object of the harshly humorous stories. In spite of the negative turn to the stories transplanted into the Almanacks by the current publisher, the humorous exaggerations included in the stories are generally recognized as building on the frontier tradition of spinning tall tales. These same stories participate in the creation of the myth of frontier life as experienced second-hand by citizens of Eastern cities. The stories told of Crockett’s life and adventures digressed so completely from any reference to the historical figure that John Seelye has characterized the mythical Davy as “a hokey hero sprung from the printer’s font.” Typical stories from the 1840s include “Colonel Crockett’s Trip to Texas and Fight with the Mexicans” in which he rides his pet bear who runs so fast “his eternal speed had scalded all the hair from his back” (1845) and the tale of “Crockett Killing Rattle-Snakes in which Crockett compares his extermination skills to the legend of St. Patrick driving the snakes from Ireland (1846). The 1846 edition was rife with tall tales, including “Crockett’s Wonderful Escape, by Driving his Pet Alligator up Niagara Falls” and “Crockett Drinking up the Gulf.”

|

|

|

| By the publication of the 1855 Crockett Almanack, the astronomical information is still provided, but the biography and animal essays have been replaced by tales of Crockett capturing a twenty-foot long buffalo and a man being swallowed whole by a crocodile. Despite their exaggeration and raucous humor, Seeley notes that the stories seem to consciously build upon archetypal mythical elements to continue the tradition of heroic storytelling that can be traced from Hercules to Superman, positioning the mythical Davy Crockett firmly in the realm of folklore hero. These later editions also increasingly include stories about other folk heroes such as Mike Fink and Kit Carson, focusing less on Crockett and more on Western myth, humor and tall tales in general.

|