|

--Ferdinand de Saussure, from Course in

General Linguistics

[The Swiss scholar Ferdinand de Saussure (1857-1913) is credited with being the ‘father of modern linguistics.’ Our class discussion will cover some of his key concepts, such as the differences between langage, langue, and parole; the differences between synchronic and diachronic theories of language; and the posited science of semiology. These concepts are also included in our on-line Glossary for 260. The selections below concern Saussure’s monumentally influential ideas about the nature of the linguistic sign. The Course in General Linguistics, a compilation of class lecture notes by Saussure’s students and colleagues, was published posthumously in 1916.] The Nature of the Linguistic Sign

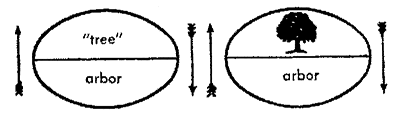

Some people regard language, when reduced to its elements, as a naming-process only – a list of words, each corresponding to the thing that it names. For example:

This conception is open to criticism at several points. It assumes that ready-made ideas exist before words (on this point, see below); it does not tell us whether a name is vocal or psychological in nature (arbor, for instance, can be considered from either viewpoint): finally, it lets us assume that the linking of a name and a thing is a very simple operation – an assumption that is anything but true. But this rather naïve approach can bring us near the truth by showing us that the linguistic unit is a double entity, one formed by the associating of two terms. We have seen in considering the speaking-circuit that both terms involved in the linguistic sign are psychological and are united in the brain by an associative bond. This point must be emphasized. The linguistic sign unites, not a thing and a name, but a concept and a sound-image. The latter is not the material sound, a purely physical thing, but the psychological imprint of the sound, the impression that it makes on our senses. The sound-image is sensory, and if I happen to call it "material," it is only in that sense, and by way of opposing it to the other term of the association, the concept, which is generally more abstract. The psychological character of our sound-images becomes apparent when we observe our own speech. Without moving our lips or tongue, we can talk to ourselves or recite mentally a selection of verse. Because we regard the words of our language as sound-images, we must avoid speaking of the "phonemes" that make up the words. This term, which suggests vocal activity, is applicable to the spoken word only, to the realization of the inner image in discourse. We can avoid that misunderstanding by speaking of the sounds and syllables of a word provided we remember that the names refer to the sound-image. The linguistic sign is then a two-sided psychological entity that can be represented by the drawing:

The two elements are intimately united, and each recalls the other. Whether we try to find the meaning of the Latin word arbor or the word that Latin uses to designate the concept "tree," it is clear that only the associations sanctioned by that language appear to us to conform to reality, and we disregard whatever others might be imaged. Our definition of the linguistic sign poses an important question of terminology. I can the combination of a concept and a sound-image a sign, but in current usage the term generally designates only a sound-image, a word, for example (arbor, etc.). One tends to forget that arbor is called a sign only because it carries the concept "tree," with the result that the idea of the sensory part implies the idea of the whole.

Ambiguity would disappear if the three notions involved here were designated by three names, each suggesting and opposing the others. I propose to retain the word sign [signe] to designate the whole and to replace concept and sound-image respectively by signified [signifie] and signifier [signifiant]; the last two terms have the advantage of indicating the opposition that separates them from each other and from the whole of which they are parts. As regards sign, if I am satisfied with it, this is simply because I do not know of any word to replace it, the ordinary language suggesting no other. The linguistic sign, as defined, has two primordial characteristics. In enunciating them I am also positing the basic principles of any study of this type.

The bond between the signifier and the signified is arbitrary. Since I mean by sign the whole that results from the associating of the signifier with the signified, I can simple say: the linguistic sign is arbitrary. The idea of "sister" is not linked by any inner relationship to the succession of sounds s-o-r which serves as its signifier in French: that it could be represented equally by just any other sequence is proved by differences among languages and by the very existence of different languages: the signified "ox" has as its signifier b-o-f on one side of the border and o-k-s on the other. [. . .] One remark in passing: when semiology becomes organized as a science, the question will arise whether or not it properly includes modes of expression based on completely natural signs, such as pantomime. Supposing that the new science welcomes them, its main concern will still be the whole group of systems grounded on the arbitrariness of the sign. In fact, every means of expression is used in society is based, in principle, on collective behavior or – what amounts to the same thing – on convention. Polite formulas, for instance, though often imbued with a certain natural expressiveness (as in the case of a Chinese who greets his emperor by bowing down to the ground nine times), are nonetheless fixed by rule; it is this rule and not the intrinsic value of the gestures that obliges one to use them. Signs that are wholly arbitrary realize better than the others the ideal of the semiological process; that is why language, the most complex and universal of all systems of expression, is also the most characteristic; in this sense linguistics can become the master-pattern for all branches of semiology although language is only one particular semiological system. [. . .] The word arbitrary also calls for comment. The term should not imply that the choice of the signifier is left entirely to the speaker (we shall see below that the individual does not have the power to change a sign in any way once it has become established in the linguistic community); I mean that it is unmotivated, i.e. arbitrary in that it actually has no natural connection with the signified. In concluding let us consider two objections that might be raised to the establishment of Principle I: >P>1. Onomatopoeia might be used to prove that the choice of the signifier is not always arbitrary. But onomatopoeic formulations are never organic elements of a linguistic system. Besides, their number is much smaller than is generally supposed. Words like French fouet ‘whip’ or glas ‘knell’ may strike certain ears with suggestive sonority, but to see that they have not always had this property we need only examine their Latin forms (fouet is derived from fagus ‘beech-tree,’ glas from classicum ‘sound of a trumpet’). The quality of their present sounds, or rather the quality that is attributed to them, is a fortuitous result of phonetic evolution.

As for authentic onomatopoeic words (e.g. glug-glug, tick-tock, etc.), not only are they limited in number, but also they are chosen somewhat arbitrarily, for they are only approximate and more or less conventional imitations of certain sounds (cf. English bow-wow and French ouaoua). In addition, once these words have been introduced into the language, they are to a certain extent subjected to the same evolution – phonetic, morphological, etc. – that other words undergo (cf. pigeon, ultimately from Vulgar Latin pipio, derived in turn from an onomatopoeic formation): obvious proof that they lose something of their original character in order to assume that of the linguistic sign in general, which is unmotivated.

2. Interjections, closely related to onomatopoeia, can be attacked on the same grounds and come no closer to refuting our thesis. One is tempted to see in them spontaneous expressions of reality dictated, so to speak, by natural forces. But for most interjections we can show that there is no fixed bond between their signified and their signifier. We need only compare two languages on this point to see how much such expressions differ from one language to the next (e.g. the English equivalent of French aie! is ‘ouch!’). We know, moreover, that many interjections were once words with specific meanings (cf. French diable! ‘darn!’ mordieu! ‘golly!’ from mort Dieu ‘God’s death,’ etc.). |